Patient Case Study: Madeline Hawkins

Madeline Hawkins was diagnosed with Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (CML) back in June 2012 after she was referred for additional blood tests following complains of pain in her feet.

Writer Philip Martin’s daughter Hilary says he saw clinical trial as “important medical adventure.”

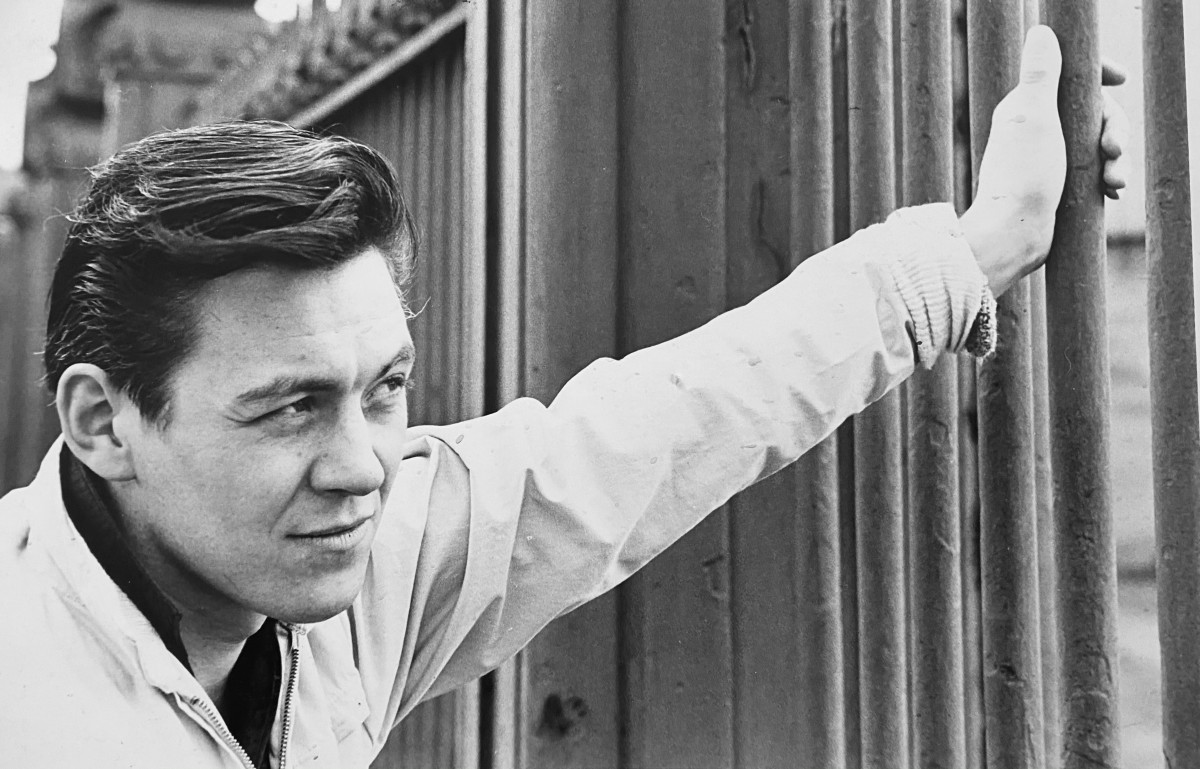

Accomplished actor-turned writer, Philip Martin, leaves behind a strong legacy of work in TV.

He created the cult hit BBC drama series Gangsters in the 1970s and later wrote two television serials for Doctor Who during Colin Baker’s tenure as the Sixth Doctor in the 1980s.

His later work included Tandoori Nights, Star Cops, Virtual Murder, several episodes of Hetty Wainthropp Investigates. Recently released was The Devil Seeds of Arador, a spin-off of his Dr Who villian which has recieved many awards on the independent film circuit.

But Philip, who lived in Lancaster, was just as proud at taking part in a clinical trial during his time battling acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and thrilled that the results would help shape treatment for those who came after him.

His own fight sadly came to an end in December 2020 – exactly two years after being diagnosed with AML.

However, he was – according to daughter Hilary – thrilled and grateful that the treatment extended his time together with his loving family and proud that his “medical adventure” would have an impact on future cases.

She told us: “Dad leapt at the chance of a clinical trial. I have to admit I was unsure at first. Did he want to spend the time he had left taking strong drugs with strong side effects and travelling to Manchester to receive them? He felt he had nothing to lose. There was a chance it could work and any chance was worth taking.

“We met with Dr Emma Searle at The Christie and her clear, straightforward, unhurried explanation of the trial process was reassuring. I could feel Dad’s positivity bouncing back.

“I felt something shift within this conversation too. Of course, he was entering the trial to try and achieve more time with our family. But he was also taking tentative steps towards realising that while his life may be coming to an end, he had the opportunity to help find a cure for people that were younger than him, people who still had lives to live and children to love.

“This clicked for him and the travel, overnight stays, physical effects of the drug became something he looked forward to and welcomed. He felt he was part of something important.

“The care given by Dr Emma and the team at The Christie was second to none. It was a Phase 1 trial and we joked that this meant he was basically a bit of a human ‘guinea pig.’ I’m not a medical expert, but I do feel being part of this trial extended his life and gave us more time together. It certainly gave him purpose and he described it as his medical adventure.”

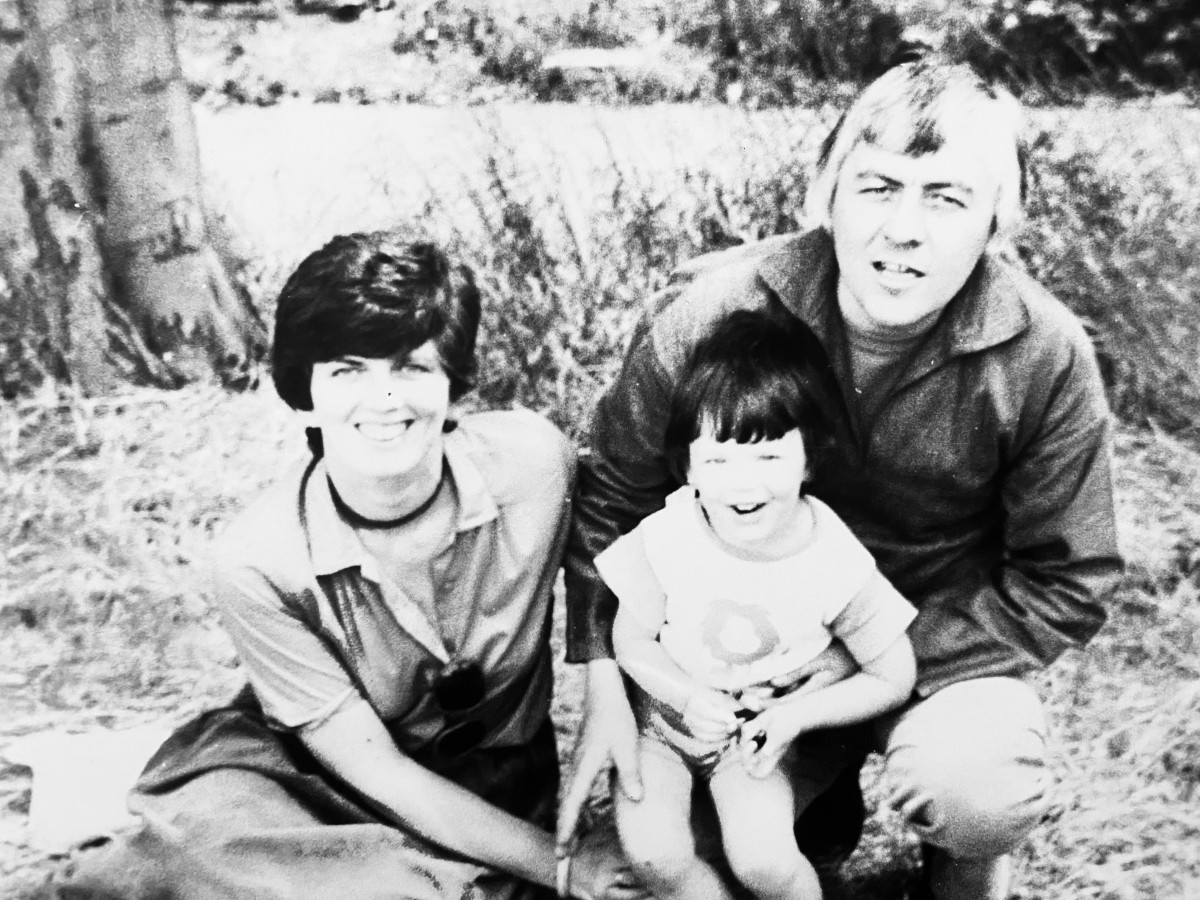

Philip, 82 at the time of his passing, first showed concerning signs on a visit to see family in the Lake District.

She continued: “He was travelling to see his eldest granddaughter Erin perform in her Christmas show. When I met him from the train he wasn’t finishing his sentences very well. When we got to the pub, he couldn’t get his words out and kept shaking his head in frustration that what he wanted to say wasn’t coming out.

“I rushed him to the outpatients department at Westmorland Hospital and was terrified he was having a stroke and would lose his speech or movement.

“My Dad was a writer and writing was his life – his worst nightmare would be not to be able to write, not be able to communicate. Thankfully, his speech started to come back to normal so they took some tests and sent us home.

We were able to catch Erin’s performance and were thrilled to grab life back in technicolour and celebrate a lucky escape.

“Just after I’d gone to bed we were woken by a phone call to say that Dad’s platelets were down to 8 and we needed to get him to hospital immediately. When the ambulance arrived around midnight my little girls heard the voices, thought it was morning time and starting getting their school uniforms on!

“At this point, we knew nothing about Platelets or Neutrophils or Haemoglobin or all the words that would become part of our daily lives. But as we waited for results I started researching online and saw that there were some scary possibilities here. In all areas of his life my Dad had a visceral fighting spirit and was determined that positivity ruled whether that be in taking the bravest choice, following your heart, putting your creative judgement out there, or just not accepting bad news.

“I felt it was my responsibility to gently prepare him that there may be something serious going on here. The bone marrow test confirmed that he had MDS and that chemotherapy would start straight away.

“I had been worried that Dad would get cross at time spent in hospital receiving the treatment he needed to keep the disease at bay but I was wrong. He came to embrace all the drugs and the blood he received twice a week as the lifeline they were. It was simple, they were essential to enable him to continue living the life he wanted to lead. As time went on this grew into something even more rewarding.

“The staff at the Day Treatment Centre in Lancaster where he received his platelets and blood created such an amazing, kind, calm atmosphere that he genuinely enjoyed his time there. He met people he liked and admired who in normal times he would never have crossed paths with.

“They celebrated his birthday with cakes and balloons, they shared his pride for the awards his work won on the film festival circuit and took joy in updates on his granddaughters Erin and Esme’s artistic endeavours.

“I will be forever grateful to the individuals involved, the public that donated the blood and the wonderful institution that is the NHS.”

The update on his condition following early treatment was excellent and Philip was on a “high” – immersing himself in his writing and enjoying the acclaim his work so richly deserved with a host of awards.

However, one year to the day of his diagnosis, there was a disappointing and frustrating news on the horizon.

She added: “Dad’s consultant at Lancaster told us that the MDS has progressed to AML and was accelerating so we would now be looking at supportive care.

“I remember the nurse taking us into a separate room after the news – and we realised that we were the patients getting the special treatment that nobody wants.

“She mentioned to us about the option of clinical trials and Dad leapt at this – and so another journey began.

“He took part in two drug trials – and the second saw him as the first person to try an increased dose of a drug that had been trialled previously – and there was worldwide interest in the results as they came through. He loved all the drama of this.

“We were of course very disappointed to learn from bone marrow tests that the AML was now accelerating quickly and the trial wasn’t helping him anymore.

“But he had no regrets, only gratitude for the opportunity to be part of it and honoured that all the expertise that the doctors and scientists had spent years accumulating had been pointed towards him and the patients behind him who are yet to be diagnosed with the same illness.”

In another quirk of fate, Philip would sadly pass away exactly another year on but not before he had “left behind a small footprint of hope for the future”.

She added: “My Dad was told that it would no longer be of benefit for him to receive platelets or blood transfusions. We asked for one last transfusion and spent a very special, emotional day together at Lancaster Day Treatment Centre.

“We described it as feeling like an award ceremony in its own right, thanking the nurses for their help and sharing the journey with us and saying goodbye.

“Dad’s consultant came and I was incredibly grateful that he spoke to Dad not with sympathy or despair but in the positive language that was the only one Dad understood and told him that what he’d achieved by living for two years since his diagnosis ‘was remarkable’.

“Then, exactly two years since he was diagnosed, I held his hand and told him how well he was doing as he passed away peacefully at home.

“For anybody that’s reading this who has experience of leukaemia please do take heart that there is a lot of life still to be lived while living with this disease. And help is on the way.

“Research is making inroads into treatments that can help. My Dad’s left a lot of love behind for his family and his work lives on but we also feel that through his involvement in the drug trials he has left behind a small footprint of hope for the future.”

Madeline Hawkins was diagnosed with Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (CML) back in June 2012 after she was referred for additional blood tests following complains of pain in her feet.

Patient/caregiver volunteers required to support a clinical trial proposal for patients with AML